As world leaders huddled at Munich’s Bayerischer Hof in February 2025, an unsettling sense of déjà vu lingered. Since 2022, the globe’s top security conference has been consumed with tackling Russia’s aggression in Ukraine.

However, this time, the once-unshakable Western unity was visibly fraying at the seams — echoing the dangerous fractures that preceded history’s most catastrophic appeasement.

Vice President J.D. Vance blindsided European allies by shifting focus from Russian aggression to railing against Europe’s so-called democratic backsliding — a rhetorical turn echoing pre-WWII America’s disdain for European “entanglements.” Trump’s special envoy Keith Kellogg doubled down, insisting the US had no plans to “physically” invite European representatives to negotiations with Russia.

The controversy exploded when reports surfaced that the Ukrainian delegation had been strong-armed into signing a vague minerals deal just to meet Vance on the conference sidelines.

Later, the Trump administration dropped another bombshell: US-Russian talks were set for Saudi Arabia — planned behind Kyiv’s back — fueling fears that Trump’s much-hyped peace deal might sideline not just Europe, but Ukraine itself.

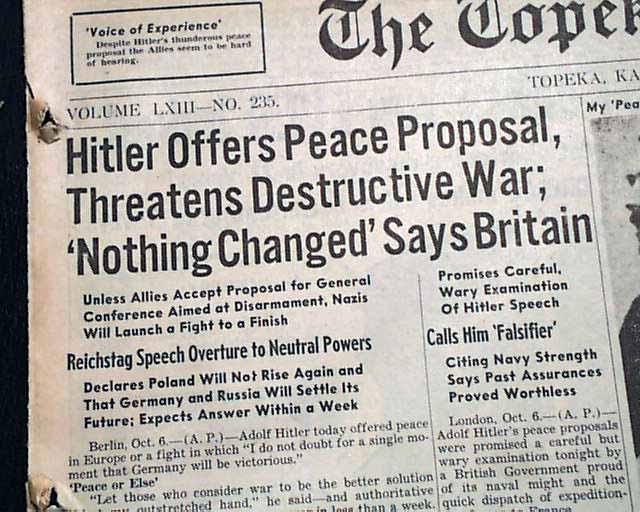

For many observers, this dramatic power play bore a suspicious resemblance to the catastrophic “peace for our time” appeasement of Hitler in 1938 — the long-standing diplomacy rules written in the blood of millions that Trump’s team seems determined to unlearn.

1. Dealing peace by selling out the victim is surrender, not a strategy

On 30 September 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and French Premier Édouard Daladier inked a fateful pact with Hitler, sanctioning Germany’s takeover of Czechoslovakia’s Sudetland in a last-ditch effort to curb Hitler’s unchecked expansion.

This infamous capitulation capped years of Hitler methodically dismantling post-WWI security guardrails. In 1936, he remilitarized the resource-rich Saar region while Western powers looked the other way. By the spring of 1938, the Third Reich had swallowed Austria.

Hitler then trained his sights on Czechoslovakia, weaponizing the German diaspora in the industrial powerhouse Sudetenland. Despite these Germans having mingled with local Slavic populations for centuries, Hitler’s propaganda machine transformed them into poster children for “reunification.”

Now, thanks to Germany’s neatly crafted hybrid strategy, Czechoslovakia — a fledgling democracy born from the wreckage of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after World War I — faces growing tension from Sudeten Germans who pushed for autonomy with Hitler’s backing.

In May 1938, the local pro-Nazi party demanded a Sudetenland referendum on joining Germany, plotting a coup to ensure the “proper” outcome. While manufacturing this separatist crisis, Hitler pitched annexation as the only peace-preserving option.

“If the Czechs resolve their issues with their national minorities, the state of Czechoslovakia will no longer interest me,” Hitler insisted just days before signing the deal. “If you like, I can give you yet another guarantee: we have no need for any Czechoslovak territory.”

Within days, Czechoslovakia was coerced into conceding territory to Hungary and Poland, all under the guise of security promises from Britain and France.

The cost of the Munich Agreement was catastrophic: it ripped away a fifth of Czechoslovakia’s land, including five million citizens, its industrial core, and vital border defenses, leaving the country exposed and weakened.

The day after inking the deal, Chamberlain returned to London, famously waving the Anglo-German Declaration he dubbed “peace for our time.” Just five months later, Hitler tore up the agreement and devoured what remained of Czechoslovakia, transforming it into a Nazi proxy state.

Slovakia and Hungary, both beneficiaries of Munich’s spoils, spent World War II as Hitler’s puppets. Both later fell under Soviet occupation and remained without true independence until the late 20th century.

The seizure of highly industrialized Sudetland handed Hitler the “arsenal of the Reich,” supercharging Germany’s war machine. The captured armaments could equip half the Nazi army, turbocharging Germany’s blitzkrieg through Poland less than a year after the fateful deal.

2. Deciding nations’ fate behind their back is a “huge mistake”

Czechoslovakia, under the resolute leadership of President Edvard Beneš, stood firm in the face of Nazi aggression. However, he understood the uncomfortable truth: he grasped a harsh truth: Britain and France, still haunted by World War I’s carnage, were too desperate to avoid another war to confront Hitler.

Beneš fought tooth and nail, hoping Britain and France would honor their alliance. But instead of standing strong, they ditched the very principles they’d championed, cutting a deal with Hitler. Behind closed doors, the country was locked out of the talks that decided its future. Its leaders were left in the dark until the deals were done.

On the evening of 30 September 1938, Britain and France — WWI victors who had crafted the postwar order — signed the Munich Agreement with Hitler, with Mussolini playing a matchmaker. Hours after the “great deal” was sealed, Beneš was handed an ultimatum: accept the surrender of the Sudetenland to Germany or face Hitler alone.

Britain and France had already made their pact, leaving Czechoslovakia with no options. No allies, no support, no hope of resisting. Faced with the threat of violent occupation, Beneš had no choice but to sign, condemning his nation to a devastating compromise.

Five days after the deal that carved up the country between Germany, Poland, and Hungary, Beneš resigned. When Hitler returned months later to devour what was left, the country’s leadership had crumbled. With no resources and no elites strong enough to resist, Czechoslovakia was an easy prey for Nazi conquest.

3. “Great deals” without security guarantees hand dictators a free pass

At Munich, Britain and France promised to protect Czechoslovakia’s borders after Germany took the Sudetenland – however, these guarantees were nothing more than paper tigers. In reality, the Munich Agreement gutted Czechoslovakia’s security. France, bound to defend the country’s borders under the post-WWI order, bowed to British pressure and walked away from its commitments.

Britain and France’s “assurances” only came after Hitler had already seized the Sudetenland — and, crucially, were entirely dependent on Hitler’s word to uphold the new borders. In fact, the country’s borders were handed over to Nazi whims.

These so-called guarantees were nothing like a formal alliance. They carried no commitment to military action if Germany violated the nation’s sovereignty. It was a far cry from France’s once-ironclad alliance with Czechoslovakia, which had now been abandoned.

Russia’s last “Ukraine peace deal” led to Europe’s biggest war since WWII. Here’s why this one could be worse.

The rude awakening came in March 1939 when Hitler swallowed the rest of Czechoslovakia. In response, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain delivered his Birmingham speech, asking whether this was “the last attack upon a small state or is it to be followed by others… a step in the direction of an attempt to dominate the world by force?”

It wasn’t until Hitler broke the “peace in our time” that Britain and France, abandoning their appeasement strategy, issued a security guarantee to Poland — the next target in Hitler’s land grab. Just five months after Czechoslovakia’s fall, Poland’s invitation to join the fray would pull Britain into war.

4. “America first” means America pays for a broken world order

Hitler’s rise — fueled even further by the disastrous Munich Conference — wasn’t just a European failure. It was made possible by a security void left by the United States, whose post-WWI isolationism and economic policies actively enabled Nazi expansion.

During World War I, the US poured 52% of its GDP into war expenditures, swelling its debt 25 times over. The backlash fueled isolationist politicians, who painted America as the victim of European bureaucrats dragging it into a costly war. Public opinion soured fast — especially if it meant more draining European conflicts.

The “Europe fatigue” dovetailed with a desire for lasting peace. The US snubbed the League of Nations, the very order it helped create, and instead threw its support behind the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact, where 16 nations vowed never to go to war again — turning its back on global responsibility.

By the mid-1930s, the US passed the Neutrality Acts, cutting off arms, loans, or credits to any warring nations — aggressors and victims. It was in this climate that the America First Committee — backed by Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh — gained power, infamously blaming “Jewish interests” for dragging America into war, even when Hitler’s army had already swallowed Europe.

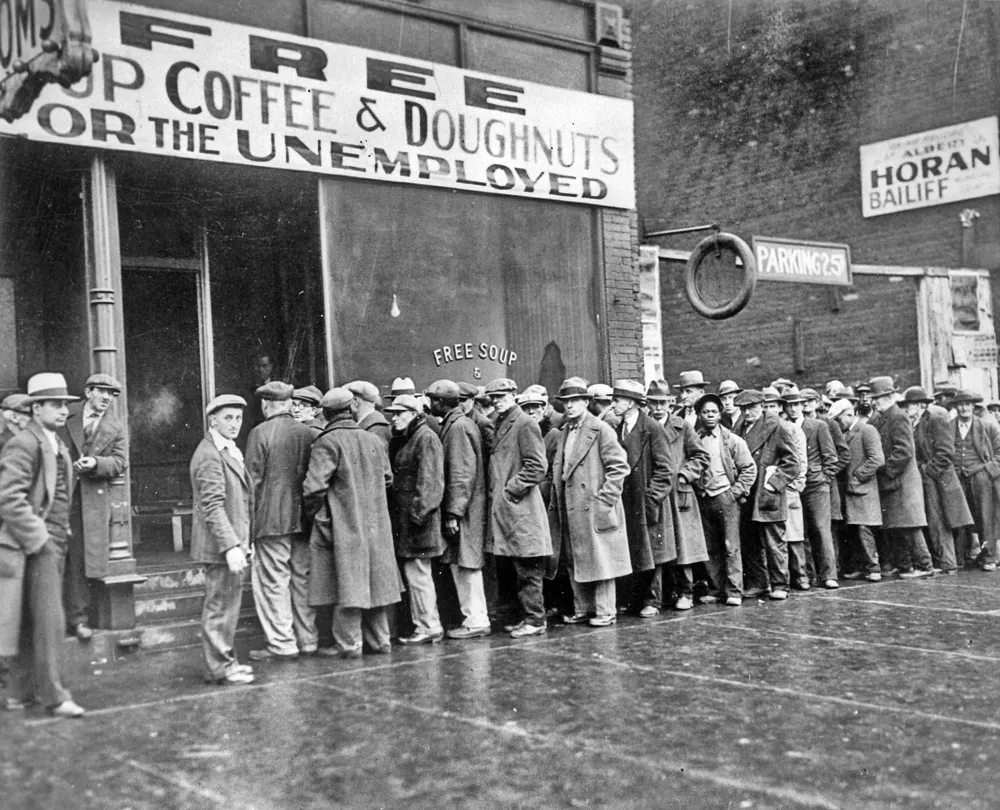

What began as a strategy to dodge foreign conflicts soon turned into an economic self-sabotage. Although loans to war-ravaged Europe morphed the US from the world’s largest debtor to a top creditor, American financiers shifted focus inward, fueling the stock market speculation that led to the 1929 crash and triggered the Great Depression.

In response, President Hoover’s Smoot-Hawley Tariff shot tariffs up 20%, the steepest hike in a century, ignoring the dire warnings from over 1,000 economists. In response, more than 25 US trading partners, led by Canada, slapped back with their own tariffs, slashing American imports by a third. By 1933, global trade had frozen, tightening the Depression’s chokehold on ordinary Americans.

America’s retreat from global affairs set the stage for a perfect storm. Recession swept through Europe, giving rise to extremist parties on both ends of the political spectrum. In Germany, the cutoff of crucial American loans for war reparations crippled the nation’s fragile post-war democracy, paving the way for Hitler. Meanwhile, Japan’s unchecked fascist expansion across Asia ramped up.

In this climate, the US Congress greeted the Munich Agreement with open arms, and President Roosevelt — upon learning of it — telegraphed Chamberlain, “Good man.” But it wasn’t Europe’s appeasement that ended America’s isolation. It was Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, two years into WWII, that pulled the US back into the global fold.

By the time America entered the war, Europe was largely buried under Nazi occupation, forcing the US to join the conflict at a much steeper cost. Defense spending skyrocketed from $1.5 billion in 1940 to $81.5 billion in 1945 – a staggering 40% of the nation’s GDP – making WWII the most expensive war in American history — but that was just the start.

After the war, the US shelled out another $14 billion to rebuild Western Europe through the Marshall Plan. At the time, while America sat on the sidelines, the USSR expanded, eventually controlling half of Europe. In the Cold War that followed, America rolled out $13 trillion on defense, proving that isolationism didn’t save the US — it only delayed the inevitable and racked up an even bigger bill for decades to come.

5. Don’t cozy up to the Kremlin to win China’s trade war – you’ll lose, big time

The Munich Agreement, which allowed Hitler to annex the Sudetenland without Western opposition, sent a loud, clear message to rising authoritarian regimes: the West was weak. As Europe buckled, Japan, sensing its chance, charged ahead with imperial ambitions across Asia, confident that it would face little resistance.

In 1931, Japan invaded China, seizing the resource-rich Manchuria to fuel its growing military. The occupation directly clashed with America’s “Open Door” policy, which guaranteed equal access to Chinese markets. The US fired back with the Stimson Doctrine, affirming China’s territorial integrity as a must to protect equal access to its markets – and America’s solid investments.

With Japan’s aggression threatening America’s key trade routes, Washington made a dramatic pivot to Moscow.

In 1933, 17 years after severing ties with the Soviet Union, Roosevelt lifted the isolation and revived diplomatic relations with the US’s communist archenemy. The goal: deter Japan while injecting a boost to America’s struggling economy by making the Soviets repay Tsarist-era debts and open their markets to American businesses.

Roosevelt’s gamble to legitimize the USSR unleashed a flood of American industry, powering Soviet industrialization with cutting-edge technology. In just a few years, US companies helped modernize Soviet agriculture and industry, tripling its capital stock.

Inside the West’s fatal peace deal with the Kremlin that exploded into the Cold War

The 1938 Munich Agreement only emboldened Japan, fueling the Nanshin-ron expansionist faction that pushed to seize Europe’s weakened colonies in Asia. By 1940, Japan had cemented its place in the global authoritarian axis, allying with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

As the Axis powers recognized Asia as Japan’s sphere of influence, America’s efforts to appease Moscow for Soviet support against Japan fell apart. Just months before Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, the USSR signed a neutrality pact with Japan, ensuring Soviet non-intervention.

Just months before Hitler’s capitulation and nuclear strikes that crushed Japan, Roosevelt doubled down with even more concessions at the Yalta conference, betting Moscow would help in the Pacific War.

Instead, America’s appeasement of the Kremlin’s “strong leader” handed the USSR keys to half of Europe and armed it with cutting-edge Western technologies, setting the stage for the Cold War. What began as a “great deal” with America’s greatest rival over Chinese trade ended up fueling the rise of the USSR, building up a geopolitical threat that would haunt Western security for decades.

One step into 1939?

This time, the stakes are higher. With Ukraine sidelined, Europe on edge, and Russia emboldened, the 2025 Munich Conference showed the world is edging dangerously close to its second 1938. History has already revealed where peace at any cost leads — and the clock is ticking for the West to decide whether it’s ready to face the consequences of waiting until 1939.

“A Russia that destroys Ukraine, in effect with American assistance, would be a very different country,” writes Yale historian Timothy Snyder. “And eventually, Europe would face a far more powerful nation — one built for war, whose leaders believe war works.”

Read also:

• “Keep calm and don’t blink first,” experts warn Ukraine as US-Russia talks begin

• As US refuses to defend Europe, Russia’s military budget now bigger than Europe’s altogether

• No Munich in Munich: Zelenskyy cozies up with republicans